by Dr.Moira Borg MD Gestalt Psychotherapist

In the norm, a parent is that person who brings up and cares for his/her child. Winnicott (1964) in fact describes the ‘good enough’ mother (parent) as the caregiver who in the beginning is totally there for the child’s needs and then starts attuning more realistically as he/she grow older.

“at the start, [the mother’s] adaptation needs to be almost exact, and unless this is so it is not possible for the infant to begin to develop a capacity to experience a relationship to external reality, or even to form a conception of external reality.”

Winnicott 1964.

As stated by Winnicott, this attunment supports the child to form a more cohesive concept of reality especially of the fact that the parent is not perfect but ‘good enough’ and can at times make mistakes. Likewise the child is more accepting of his/her fallability and thus less prone to feel ashamed of his/her failures.

The most common issue that brings children to therapy is when one or both of their parents are not ‘good enough’ and then their needs, at times even the most basic ones, suffer tremendously. When 12 year old Emily (not her real name) was brought to therapy she was visibly underweight and withdrawn; her mother was also very concerned about her mood swings especially her low moods which were usually associated with poor eating habits and social withdrawal.

Emily was born out of a unstable teenage relationship which only lasted a few months. Despite being of a very young age, her mother dedicated herself to bring her up against all odds mostly her family’s shame and complete inacceptance of the child and the father’s irresponsibility and neglect. Emily performed well at school, had a number of friends and quite a healthy relationship with her mother and long-standing partner and her extended family. However, most of the time she seemed to attract a lot of bullying, even of quite an aggressive nature. After some sessions where we slowly built our therapeutic relationship and worked on her feelings around angry people mostly her grandmother and a number of schoolmates she expressed a specific need to work on her relationship with her father.

Children are very loyal to their parents as the parent-child relationship is of vital importance to the stability and psychic survival of the child. Thus they are ready to project responsibility on others and themselves to protect even the most abusive and neglectful parent. So when a child or young individual is ready to process the reality of a parent’s abuse, I know that it would be coming from a place of deep pain, shame and internal conflict in having to acknowledge that either him/herself or his/her parent is not ‘good enough’.

Emily’s relationship with her father is very tense and distant. She visits him every weekend in the home he has set up with his new partner and their young daughter. Emily confesses that what drives her to keep the contact is the deep bond she shares with her half-sister and the affection she holds for her father’s partner. She shares with deep sadness that her father hardly acknowleges her when she visits, gives more attention to her younger sister and is very abrupt and at times aggressive the few times he communicates with

her. She also describes experiences of abuse and neglect when he regularly ignores her pleas to prepare her something to eat and when he expects her to sit still for long periods of time without anything to distract her.

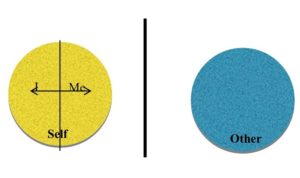

When a child is faced with ongoing abuse, he/she has to live with the shame of not being cared for the way he/she needs. To avoid the pain and desolation associated with such shame, the child splits hiding his/her real self, including his/her needs, and projecting a false self in a desperate attempt to protect him/herself from the toxicity in his/her environment.

We use toy animal models to explore the relationship between her and her father. Emily is very sharp and emotionally intelligent for her age and she describes different aspects of her father’s personality using different animal models where the shark represents his agressive aspect, the giraffe his power and strength and the dog his controlling nature. These aspects of him surround the small seal, representing her, leaving no room for escape or freedom.

We explore how these aspects of him affect her. She describes how the control suffocates and frustrates her at times to the point of anger and how his ‘power’ and aggresivness terrify her. From her body experience it is clear that the fear is very prominent and in fact she adds a crocodile snapping at the baby seal to highlight this further so I decide to explore this anger issue further using drawing as a medium.

We explore how these aspects of him affect her. She describes how the control suffocates and frustrates her at times to the point of anger and how his ‘power’ and aggresivness terrify her. From her body experience it is clear that the fear is very prominent and in fact she adds a crocodile snapping at the baby seal to highlight this further so I decide to explore this anger issue further using drawing as a medium.

Techniques such as drawing or the use of toy models or puppets are very beneficial in supporting children (and even adults) in expressing feelings they either find hard to express, usually out of love or loyalty, or are not aware of at all – projective techniques that support the emergence of the real self. In Emily’s case both media supported her to express pent up feelings and also opened up avenues for further work on how she could face irrational anger and aggressivness including bullying.

At the heart of Gestalt therapy there is the quest for contact using both the therapeutic relationship and specific techniques to aid expression and subsequent awareness and change. The overall experience gives the child a new exposure to a healthier relationship, and thus a different way of being in the world. It is this support of taking in the reality of the world in its limits that isafter all at the heart of ‘good enough parenting’ and it is important for the therapist to give the child what the parent would not have given. Likewise the child’s needs would have been met and then he/she can proceed with his/her normal development.