by Dr.Moira Borg MD Gestalt Psychotherapist

Ema was 15 when she was brought to therapy by her mother due to low weight and severe anxiety especially around her academic performance, appearance and social acceptance. At the time she had just started sixth form after performing exceptionally well in her Ordinary levels and her dream was to enrol in medical school. She was an only child and lived with her parents who both held manegerial roles.

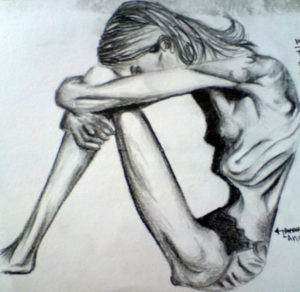

Ema left a particular impact in our first meeting. She was tall and very thin, her skin was sallow and she was dressed in dull colours. As she sat near her mother, she was literally sunken in her chair as if she had a pit in her stomach area around which her whole body curled. Her mother on the other hand was larger than life, with wild curly hair and flamboyant clothes and jewellery. While Ema sat totally withdrawn in her space, her mother was taking all the space in the room in a way that even I had to struggle to fit in. Looking at them at that particular moment, it felt as if the mother had sucked out all the youth and life out of her daughter leaving her shrivelled and listless.

With subsequent sessions with daughter and mother the family dynamic became clearer. The parents had a very strained relationship and used their daughter to communicate between them. It was clear that both parents had little emotional capacity to support their daughter so while Ema had everything material she needed, she had to fend for herself from the age of 12, even preparing her own food and clothes. With time she found a way to counteract this deep loneliness and lack of contact by imagining she was part of the ‘family’ of the series she watched on a regular basis and by ‘relating’ with her dolls and soft toys.

Even though anorexia nervosa is listed on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as a mental disorder, I believe that it is not an individual disorder but a malfunctioning of the whole family which is expressed in one family member. As a result in my work with Ema I focused on the following dynamics:

- the setting up of a good therapeutic relationship – since anorexia nervosa results from dysfunctional family relationships.

- supporting the family to understand their present dynamics and to form healthier contact – addressing the entanglement

- supporting the integration of the self and heal the splitting which results from such dynamics by raising the awareness to the present problem, including the parallel process of how the client contacts the food (control) and relates to the therapist, getting the client in touch with reality (internal physical/somatic, emotional states and splitting, contact and boundary disturbances) and support her to solve any associated issues.

The role of therapy is thus to support the client into a mutual and fulfilling experience with her environment without adapting to it.

THE CORE OF THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTION – THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

The quality of the therapeutic relationship is of paramount importance especially considering that the root of the anorexic ex perience lies in that first relationship with the caregiver. One pitfall to avoid in the anorexic experience is encouraging the same confluent/enmeshed relationship that the child has had with the mother (McDougall, 1989).

perience lies in that first relationship with the caregiver. One pitfall to avoid in the anorexic experience is encouraging the same confluent/enmeshed relationship that the child has had with the mother (McDougall, 1989).

THE INITIAL PHASES – MOVING OUT OF THE ENTANGLEMENT

Ema’s relationship with her mother was the theme of most of our work in the early phases of therapy. Ema consistently claimed that as far as she could remember she never felt safe with her and found it very difficult to trust her. I also became aware that the father was an absent figure in this dynamic. Apparently he was at work most of the time even on Sundays. Ema was thus left yearning for the family “everyone else” had (Roos, 2001) and doing her utmost to keep it together (Byng-Hall, 1985). Letting go for Ema meant losing herself and all she had.

“That’s why I’m so scared of letting go ….Because if I let go (of food ) I’m scared of feeling the real void and emptiness…”

After some months in therapy however, Ema began to express her frustration and anger at being caught in the space between her parents and their constant reliance on her. Apparently her new experience of a healthier relationship with me caused this shift in awareness that she was not in her rightful place and that perhaps it was not up to her to keep the family together. One day she asked me for a face-to-face session with her mother where with a strong voice she told her to stop using her as a means to talk to her father; she asked her in the same firm voice to tell her dad to do the same. By putting such a boundary to her mother (and father) she was breaking the mother-daughter confluence where her emotions, feelings and thoughts were of no consequence and where her body became the sole agent of communication with the world, the same way it did before she learnt to speak (‘somatisation’) (McDougall, 1989). As a result, she could get in touch with her emotions and not only verbalise them but also direct them to the person who caused them in the first place.

the sole agent of communication with the world, the same way it did before she learnt to speak (‘somatisation’) (McDougall, 1989). As a result, she could get in touch with her emotions and not only verbalise them but also direct them to the person who caused them in the first place.

AWARENESS AND INTEGRATION OF THE SELF

Having formed a good relationship with Ema and supported her out of the unhealthy confluence with her mother, it was easier for her to express the pain, insecurity and shame around her body perception and experience. In one session she shared:

“the more I meet people,the more I feel insecure about myself and my body image….all I think about is how ugly and fat I am….. I feel too suffocated and pressured.”

The obsessive focus on herself was very evident as was the confluence with and excessive influence by her environment; in fact she compared herself to clay, easily moulded by others. During one session I asked her to draw how she experiences herself. Using a pencil she drew two faint ‘fat’ circles at one end of the page and some firm straight lines at the other; the fat circles were her and her mother and the thin straight lines were the other girls and women she knew.

“.….I’m fighting a constant battle with food….and hating my body image.……… All I want to do is break down. Because I’m tired. I’m tired of trying to be liked by everyone….. Im tired of beating myself up every time I look in the mirror, I’m tired of feeling like crap every day because I’m not like other more attractive girls, more successful people..… I can’t change who I am……”

In my early interventions, I supported her to become more aware of her eating patterns (food diary) and its repercussions, including the physical, emotional and social aspects, without recreating the shaming experience, induced by society and her family. Months after starting therapy, Ema started to eat more, gain weight and her menstrual cycles returned to their usual pattern; this was a clear indication that our therapeutic relationship was having its benefits. In the same parallel process as with her anorexia, she was nourishing more on food the way she was on my presence (Merian, 1991). Although encouraging this outcome was not the end of therapy but a positive step in a very long and tortuous journey towards her self integration which is still ongoing after 7 years.

“I cannot say that I’ve managed to remove all that shame I’ve carried for so long ..and don’t think it will ever go away ..I am ashamed about a lot of things …I was scared to face them …..learn to accept it ..to face it and have the courage to say that yes I am vulnerable, I have failed and I have felt ashamed over and over again…..this is what I want….I want self acceptance.”

Ema’s parents separated a year after she started therapy and she decided to move in with her father in a much smaller house as she found it difficult to move in with her mother and her new partner. She now goes out most of the weekends, has a small circle of friends and even went to Ireland for 5 months with three fellow students on an Erasmus program; there she met her first boyfriend and had her first experiences in love and intimacy. They are still together to this present day.

This is where the journeying butterfly is at the moment, more aware of her beauty even if she still struggles to adapt to living more in the light after having been in the darkness for so long.

References:

Byng-Hall, J. (1985). The family script: A Useful Bridge between Theory and Practice. Journal of Family Therapy: 7: 301-305

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. 2013

McDougall, Joyce. (1989). Theatres of the Body: A psychoanalytic approach to psychosomatic illness. Free Association Books

Merian, Sally. D. (1991). The Use of Gestalt Psychotherapy in Patients Suffering from Bulimia. The British Gestalt Journal, 1993, 2, 125-130.

Roos, S. (2001). Theory Development: Chronic Sorrow and the Gestalt Construct of Closure. Gestalt Review, 5(4):289–310, 2001.